How Ireland Became Catholic and How Ireland Has Remained Catholic

Catholic Ireland;

how Ireland became Catholic

AND

how Ireland has remained Catholic

by Rev. P.J. Kirwan

Published in 1908

Published in 1908

In the Pastoral Letter of His Eminence Cardinal Logue for Lent, we find the following- “A great work is being done by the Catholic Truth Society of Ireland for furnishing the people with such reading as will deprive them of all excuse for resorting to the poisoned sources from which so many were wont to imbibe an irreligious sensual, and often corrupting draught. Their efforts must and should receive every support. Whenever I see in a church the well known box destined for the distribution of their publications, I take it as a clear proof of the pastor’s zeal for the best interests of his people”

“It is well known”, writes His Grace the Archbishop of Tuam, “that various printing presses in Great Britain daily pour out a flood of infidel and immoral publications, some of which overflows to this country. We have a confident hope that the Society’s (C.T.S.I.) publications will remove the temptation of having recourse to such filthy garbage, will create a taste for pure and wholesome literature, and will also serve as an antidote against the poisons of dangerous or immoral writings”.

“Allow me, dearly beloved,” writes Dr. Fennelly, Archbishop of Cashel, in his Lenten Pastoral, 1903, “before concluding, to say something in favour of the Catholic Truth Society, which has been got up for the purposes of counter-acting a growing taste amongst our people for an overflow of filthy literature from England, and other countries. Its publications are racy of the soil, and very varied in point of subject: and, as far as I can judge, are, in many instances, of high literary merit. I ask priests and people to support the Catholic Truth Society, by taking and reading its publications.”

St. Patrick was born around the year 397, and when he was but 16 years of age he was seized upon and sold as a slave to a man in the County Antrim. It is believed he spent his six years in slavery, as he was taken captive more than once. Who can conceive his sufferings and privations during those six long years? A noble youth, who had been brought up with the tenderest care, and who had been accustomed from his earliest infancy to the enjoyment of all that could render life pleasant and happy – for we must remember that St. Patrick was of distinguished birth – is suddenly torn away from his parents and friends, and is sent into slavery to tend cattle in the far north of Ireland, There he has no one to help or to pity him, and he has to bear the greatest trials and sufferings; but patiently and bravely did he endure all.

At the end of the Six years when he had learned the language and customs of the people amongst whom he served, when he had exercised himself in the practice of humility and every virtue, and the designs of Providence had been fully accomplished in his regard; when at length he happily escaped from captivity and returned to his home, what did he do?

Did he remain with his friends amidst comforts and joys, rendered all the more dear since they had once been lost? No! A voice which comes from afar on the Western breeze – the voice, as it were, of many united in one holy strain – says to him: We entreat thee, O holy youth, to come and walk amongst us. “It was the voice of the Irish,” says the Saint, in the Book of his Confessions, “and I was greatly affected in my heart”. He arose, and once more leaving home, went forth to prepare himself for his great mission.

Once completing many years of study, he went to Rome to receive his grade, or ordination, and to visit the Shrines of the Apostles and the successor of St. Peter – Christ’s Vicar on earth. Having been ordained Priest and afterwards consecrated Bishop, Saint Patrick set out at once for the scene of his labours. He came to Ireland once more, no longer captive, but free, and destined to break the nation’s chains. No longer dragged thither the unwilling slave of men, but borne by irresistible love, the willing slave of Christ. And soon he gives proof of his great bravery, for he had not been in Ireland before he resolved, by one bold and decisive act, to effect the overthrow of paganism in the country.

As Easter approached he prepared to celebrate it near Tara, which was the royal residence and the chief seat of paganism and druidism.

King Leaghaire, who was monarch of all Ireland, was holding his court at Tara. The druids and magicians were with him, and they were keeping a great pagan festival which required that the fire of every hearth in Erin should have been extinguished on the previous night, and it was forbidden, under pain of death, that it should be rekindled before the great fire was lit of Tara. This pagan festival corresponded, as regards the time of its celebration, with the great festival of the Pasch or Easter, which St. Patrick was about to celebrate.

The Saint kindled his paschal fire of the hill of Slane, within sight of Tara. The king and his chiefs saw the light flashing over the plain. The druids answer that if the light was not extinguished that very night, it would be never be extinguished in Erin, and the man who had kindled it, they said, “would surpass kings and princes.”

Alarmed at this answer, the king instantly dispatched messengers to summon St. Patrick into his presence. The chiefs seated themselves in a circle on the grass to receive him, and on his arrive, one alone stood amongst them, struck by his venerable appearance, stood up to salute him. The others, however, listened attentively while the king asked the Saint many questions. The druids contended with him and insolently denounced the doctrine of the Blessed Trinity, which St. Patrick earnestly defended.

The king is said to have asked the Saint for an example to explain to him how there could be Three Persons in the One God. It was then, according to an ancient tradition, St. Patrick picked up the shamrock and pointed to three leaves with the one stalk or stem. This is why the shamrock is worn on the National Festival and is held in such veneration. Though Leaghaire refused to believe he gave St. Patrick full liberty to preach, and to receive all who might be willing to become Christians.

St. Patrick by his miracles silenced the druids and put an end to their power. Great numbers presented themselves to be instructed and baptized, amongst others the chief druid. Their example was followed by more men, and soon St. Patrick’s converts might be counted by thousands – all remarkable for their great faith and fidelity.

As an example, an incident that took place at the baptism of a young prince may be related. St. Patrick carried in his hand, according to his custom, his great staff or crosier. At the end of this crosier there was a sharp iron spike by means of which he could fix the staff in the ground while he preached or exercised his episcopal functions. On this occasion, however, he struck it through the prince’s foot, which he nailed to the earth, without perceiving his mistake until the ceremony was over, and then as he was about to lift his staff, as he thought, out of the ground, he discovered it buried in the foot of the prince. The brave young man had borne the torture in silence, and when the Saint expressed his deep regret and asked why he had not complained and made known to him what had happened, he simply replied that he thought it was part of the ceremony and did not regard it as of much consequence. He must have thought since Our Lord’s hands and feet had been pierced for us, his feet should have to be pierced in turn.

We have another example of the fidelity of the people in St. Patrick’s coachman or charioteer, who lost his own life in saving the life of the Saint. The coachman having heard that a certain chief was lying in wait to kill his master, he without telling St. Patrick anything about it, got him to change places with him in the chariot, by saying: “I am now a long time driving for you, my good master, Patrick: will you take my place today and let me sit to rest myself in your place?” St. Patrick readily consented and his faithful servant was killed in mistake for himself.

We cannot be surprised that the faith should spread rapidly amongst such a brave and noble people, and that soon the whole country was converted, and this was accomplished in the lifetime of St. Patrick. He found Ireland pagan; he had the happiness to see it wholly Christian before his death but it was not without the greatest labour that he effected this wonderful change. The Saint gave himself little rest. The day he spent in preaching; the greater part of the night he devoted to prayer. Like St. Paul, he even found time for manual labour. Everywhere he went he destroyed the pagan altars and temples, and founded churches, and ordained priests and bishops. He worked the greatest miracles by healing the sick, curing the blind, and even raising the dead. He is said to have raised nine dead persons to life.

When after a long and glorious career, St. Patrick reached the end of his labours and went to his reward, his care for his people did not cease, nor their devotion for him. While on earth he prayed that the faith of those whom he had converted should never fail, and he begged of God that he might appointed the Judge and Protector of the Irish people. Well has his prayer been heard, and faithfully has he continued to watch over his people, and true have his people been to the faith which he preached to them. Space would not permit to recount all that St. Patrick’s people have done and suffered for the faith, since his coming to the present day.

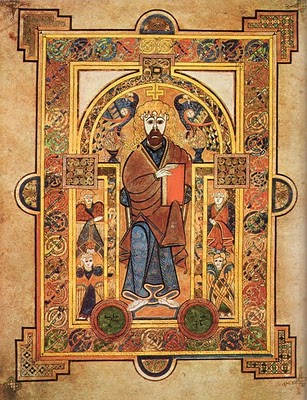

Book of Kells

For three hundreds after St. Patrick, Ireland was famous for her sanctity and learning, and was known as the “Island of Saints and Scholars”. During that time the youth of France, Germany and Switzerland flocked to Ireland, and a French writers tells us that they were all received with the greatest hospitality; but “to the English students”, says Ven. Bede, “Ireland showed her greatest generosity”. The whole country was covered with schools and monasteries and all was peaceful and happy; but during the next three hundred years there was a sad change. The Danes invaded the country, destroyed the churches and monasteries, put the monks to death, and continued to lay the country waste, ‘till the famous Brian Boru succeeded in defeating them, and in driving them out of Ireland.

What an example do we not find in him of a true Christian hero? On the day of the Battle of Clontarf, when he was about 80 years of age, he upheld the crucifix before his army in the morning and he died in its embraces before the sunset!

The Danish invasion was soon followed by another invasion and three hundred years more of war and bloodshed and that was again followed by nearly three hundred years of persecution.

During all that time Ireland continued to give the grandest proofs of her faith and bravery. She has clung to the old religion with unexampled fidelity, and what she has suffered for the faith can scarcely be imagined or described; but those unhappy days of persecution (thank God), have passed away, and now if Catholics fail to practice their religion, the fault is altogether their own. What excuse can the Catholics of the present time have when they consider the sacrifices our forefathers had to make and the sufferings and privations they had to endure?

We have seen how Ireland became Catholic, through our glorious St. Patrick. We shall see in the pages that follow how Ireland has remained Catholic throughout the terrible days of persecution.

HOW IRELAND HAS REMAINED CATHOLIC

“Never has a whole nation”, says Cardinal Moran, “suffered more for the faith than Ireland; and nowhere has fidelity to God and loyalty to the Holy See, amid unparalleled sufferings and national humiliations, achieved more glorious victories or has been crowned with happier results

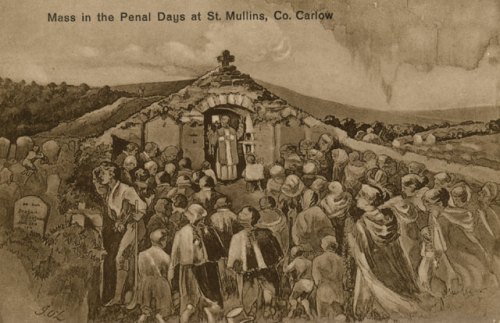

“For poor Ireland the day of trial came, and came with a vengeance; the foe, the stranger, the heretic, covered the land; the schools and monasteries, from which on hill and dale prayer and sacrifice ascended like sweet incense before the Almighty, were razed to the ground, and the holy inmates either put to the sword or exiled, to see no more the shores of their beloved Erin. The holy altars were desecrated, the churches were demolished, and the sword, the rack, and the gibbet reeked in the blood of Ireland’s Bishops and Priests. Driven from every home, the mountain fastnesses, the bog and the forest protected the priest and his faithful from the axe and the halter; here each cave became a sanctuary, and each rude rock an altar, on which was offered, with the wide heavens as a canopy, the infinite Sacrifice of Redemption. And many a time surprised to this lonely retreat, the good shepherd was torn from his loving and faithful flock, and martyred on the very rock on which before he immolated the Lamb of God!

“Nor was the storm a passing one; for several centuries it swept over the land in unabated fury, and when the tempest appeared to lull the danger became the greater; when the sword was blunted, when the scaffold appeared loath to shed more innocent blood, when brute force could not shake the Irish heart, now flowers were strewed along the road to apostasy, tempting rewards were held out, and the fatal poison was covered in the honeyed cup of learning; but infinite thanks to the Almighty and thanks to the ‘army’ of Irish Saints, with St. Patrick at their head, who before the throne of God prayed for fidelity and perseverance for their suffering and dying countrymen, the sons of St. Patrick were true to the faith; they disliked and rejected the proffered boon of apostasy, and with holy indignation cast from their lips the poisoned draughts of the heretic”(1)

“During the centuries of persecution by the Danes, later on by the Saxons, and especially the fierce wars of Elizabeth and Cromwell, nothing sacred escaped the hands of the spoilers, Hence, libraries contained priceless treasures of books and manuscripts, recording toe history of centuries, shared the fate of the monasteries, and were reduced to ashes. Every ingenuity was resorted to destroy the records of past and present, and obliterate or sully the memory of the illustrious dead. Hence, during these many years of persecution, thousands of Irish shed their blood for the Faith. Their names will never be known on earth. Their glorious martyrdom is registered only in the book of Eternal Life” (2)

O’Sullivan Beare, in his work published in Lisbon in 1618, writes: “Notwithstanding the trials beset him the holy Prelate, Dr. O’ Hurley, administered the Sacraments with incredible zeal and labour to the flock entrusted to his care, and continued to preach the Gospel with great success. For two whole years English spies sought every opportunity to seize his person, but their plans were frustrated by the fidelity of the Irish Catholics. In order to escape notice, he wore generally a secular dress, as, indeed, all bishops and priests were obliged to do in England, Ireland, and Scotland, ever since this persecution first broke out …….Dr O’Hurley was arrested at Carrick-on-Suir in September, 1583. Thomas Butler, surnamed the “Black Earl of Ormonde”, protested against this injustice and used every exertion afterwards to obtain the Archbishop’s release, but all to no purpose……The Archbishop was hurried off to Dublin, and kept bound there in chains in a dark and loathsome prison up to Holy Thursday of the following year, when he was brought before the Lords Justices Loftus and Wallop. At first they received him kindly, and promised a free pardon and promotion in the Church if he denied the Spiritual power of the Pope, and acknowledge the Queen’s supremacy. ‘He had resolved’, he replied, ‘never to abandon, for any temporal reward the Catholic Church, Vicar of Christ, and the true faith’. Loftus and Wallop, seeing that promises would not avail, had recourse to arguments……If arguments failed to convince him, they said, other means must be tried to change his purpose. The holy Prelate was then bound to the trunk of a large tree, with his hands and feet chained, and his legs forced into long leather boots reaching up to his knees, as they used to be worn then. The boots were filled with salt, butter, oil, hemp, and pitch, and the martyr’s body stretched on an iron grate over a fire, and cruelly tortured for more than an hour. The pitch, oil, and other materials boiled over; the skin was torn off the feet, and even large pieces of flesh, so as to leave the bones quite bare. The muscles and veins contracted gradually, and when the boots were pulled off, no one could bear to look at the mangled body. Still, the holy martyr, notwithstanding these tortures, kept his mind fixed on God and holy things, never uttered a word of complaint but quietly submitted to all these trials with the same serene countenance to the very end.

“The soldiers were instructed to take him to the place of execution before daylight, and to hang him at an early hour, when the people could have no notice. These orders were carried out strictly. Only two of the citizens followed their pastor, and a friend who had watched over him with the greatest anxiety from his first arrest. The rope with which they hanged him was made of twigs, cut on Stephen’s Green, which was then an osiery, in order to prolong his sufferings on the scaffold.”

On the 3rd of May, 1681, Dr. Oliver Plunkett, the Archbishop of Armagh, and Primate of all Ireland, was arraigned at the King’s Bench Bar (London) “for high treason: for endeavoring and compassing the King’s death, to levy war in Ireland, and to alter the religion there, and to raise an army of 70,000 men to support the French invasion, and kept in house 100 priests to take charge of the French landing.” His reply was that his house was a thatched cabin of two rooms: the total number of priests in his whole diocese was only sixty-two, and his own annual stipend was from £25 to £40. “It is well known,” says the Archbishop, “that in all the province, take men, women, and children of the Roman Catholics, they could not make up 70,000…….As I am a dying man and hope for salvation by my Lord and Saviour, I am not guilty of one point of treason they have sworn against me, no more than the child that was born yesterday”.

The Lord Chief Justice pronounced the following sentence……”Therefore, you must go from hence toe the place from whence you came, that is to Newgate, and from thence you shall be drawn through the City of London to Tyburn, there you shall be hanged by the neck, but cut down before you are dead, your bowels shall be take out, and burnt before your face, your body be divided into four quarters, and be disposed of as His Majesty pleases”. After hearing this fearful sentence our holy martyr cried out, “God Almighty bless your lordship. And now, my lord, as I am a dead man to this world, I was never guilty of any of the reasons laid to my charge, as you will hear in time”. In his dying speech he again asserted his innocence of any treasonable plot, and declared that he freely forgave his false accusers, after which he prayed aloud for the king, etc. “Having concluded his discourse,” continues his biographer, “the sentence was carried into execution and his happy soul sped its flight to enjoy eternal repose”.

During his last days he wrote some beautiful farewell letters to his relations, in one of which he speaks with the great gratitude of the English Catholics, “who spared”, says he, “neither money nor gold to relieve me and did for me on my trial all that even my brothers could do” . He was the last of the long train of martyrs who suffered in England.

We are not able to record the martyrdom of more than one who suffered later in Ireland – Father Nicholas Sheehy, P.P., of Clogheen, Co. Tipperary. He was born in Fethard in 1728, educated in France, and led to scaffold at Clonmel in 1766, under the accusation, indeed, of various crimes, but in reality through hatred of the Catholic Church, of which he was a devoted priest. He had some time before been arrested and indicted for saying Mass, and exercising the other duties of his holy office, but for want of sufficient evidence had been acquitted. He was now accused of high treason and a reward of £300 was offered by the Government for his arrest. Conscious of innocence, he addressed a letter to the Government offering to place himself in their hands for trial on such a charge, on condition that his trial should not take place in Clonmel, where his enemies had sworn to take away his life, but in the Court of the King’s Bench, Dublin.

This condition was accepted, and he was according tried in Dublin, and honourably acquitted, the witnesses who were produced against him being persons of no credit, whose testimony no jury could receive. He was no sooner declared “not guilty” than his enemies had him arrested on a new accusation. An informer named Bridges had disappeared, and was supposed to have been murdered, and Father Sheehy was now accused of having murdered him. It is difficult to free the Government from complicity with his accusers when they permitted this case to be sent for trial to Clonmel.

There were none to accuse him but the same infamous witnesses whose testimony had been discredited in the King’s Bench. Moreover, on the night of the supposed murder, Father Sheehy had been far away from the place assigned for the crime, with Mr. Keating, a gentleman of property and unimpeached integrity. This gentleman no sooner appeared in court to attest this fact, than a Protestant minister named Hewetson stood up and accused him of a murder which had taken place in Newmarket. Mr. Keating was himself immediately arrested and hurried off to Kilkenny Gaol. In due course he was tried and acquitted, there not being a shadow of evidence against him; but the enemies of Father Sheehy had gained their purpose, for in the meantime sentence had passed upon him, and he had suffered the extreme penalty of the law. By many Protestants of his own district Father Sheehy was held in the greatest esteem. His last place of refuge was in the house of a Protestant farmer named Griffiths, whose house adjoined the churchyard of Shandraham, where Father Sheehy’s remains now repose. During the day time Father Sheehy used to be concealed in a vault of the churchyard, and at night he entered the house, where a large fire had to be kindled, so benumbed was he from the hardships of what might be justly styled his living tomb.

On March 15th, 1766, the second day after the sentence, he was hanged and quartered at Clonmel. A few weeks later, three culprits, under sentence of death in Clonmel Gaol, attested that pardon was offered them if only they would accuse Father Sheehy of being guilty of the crime imputed to him. Father Sheehy made no secret of his sympathy with the people in their impoverished and oppressed conditions, but he was wholly innocent of the crime with which he was charged, so that he was a true patriot as well as a Martyr-Priest.

“Space will not permit to set forth in detail the long series of enactments which were sanctioned in successive Parliament to oppress and to degrade the Irish Catholics. It will suffice to sketch briefly some of the distinctive features of the Penal Code, and to glean from official record and other authentic sources a few facts which may serve to illustrate at the same time the bitterness of the persecution and the true heroism of the sufferers”.

“The Penal Code was a complete system,” says Burke, “well digested and well composed in all its parts. It was a machine of wise and elaborate contrivance, and as well fitted for the oppression, impoverishment, and degradation of a feeble people, and the debasement in them of human nature itself, as ever proceeded from the perverted ingenuity of man”. (3)

“It would be difficult,” says Mr. Lecky, “in the whole compass of history to find another instance in which various and such powerful agencies concurred to degrade the character and to blast the prosperity of a nation”.

Dean Swift, Godwin Smith and MacKnight give the same testimony, and (Lord) John Morley adds: “Protestants love to dwell upon the horrors of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, of the proscriptions of Philip the Second, and of the Inquisition. Let them turn candidly to the history of Ireland, from 1691 down to 1798, and they will perceive that the diabolical proscriptions of the Penal Laws, and the frenzied atrocities with which the Protestants suppressed the Catholic rising at the close of the century, are absolutely unsurpassed in history. The Penal Code has often been transcribed. In a country where the toleration of Protestantism is constantly overvaunted, it can scarcely be transcribed too often”. (4)

During the whole of the eighteenth century the Penal Laws may be said to have been in full force throughout the length and breadth of the lands. By the Treaty of Limerick was practically placed on a footing of perfect equality with the English settlers in the island. They were granted freedom of religious worship and the use of arms, and were confirmed in their proprietorial rights and privileges. They were entitled to sit in Parliament, to vote at elections, to practice law and medicine, and to engage in trade commerce.

This treaty was shamefully violated: Catholics were excluded from both Houses of Parliament, an oath of abjuration being required. All “Popish” holidays were abrogated and all “Popish” citizens were ordered to be disarmed. It was enacted that no Catholic should be allowed to keep a horse of the value of more than £5, and the Act provided that no matter how valuable might be the horse owned by a Papist, any Protestant might seize it on the payment of £5 5s. A special Act was passed banishing the Catholic bishops and the regular clergy; should they return from banishment they incurred the penalty of treason. 454 of the regular clergy were sent into exile in 1698. By further Acts the sending of Catholic children to the Continent was indicted; Catholics were disqualified from the legal profession, and marriage of Protestants with Catholic wives was required. By a special provision in this last enactment, any Protestant marrying a Catholic wife was to be deemed a Papist and was disabled from sitting in either House of Parliament, “unless such person so marrying shall within a year after such marriage procure such wife to be converted to the Protestant religion.” Some years later a Committee of the [colonial] Irish House of Commons decided that under this Act Protestants married to Catholic wives were disqualified even to vote for members of Parliament. On the accession of Queen Anne other penal Laws followed in quick succession. In 1703 an Act was passed that practically abolished the Catholic landlords of Ireland.

“The whole power and property of (Ireland) has been conferred by successive monarchs of England upon an English colony, composed of three sets of English adventurers who poured into this country at the termination of three successive rebellions. Confiscation is their common title; and from their first settlement they have been hemmed in on every side by the old inhabitants of the island, brooding over their discontents in sullen indignation.” John Fitzgibbon, Earl of Clare, urging adoption of the Act of Union, 10th February 1800.

The whole landed property of the kingdom was transferred to men filled with bitter hatred of the Catholic Faith; the natives who remained true to their creed were mercilessly tramped on. Dean Swift, who was eye-witness of what he describes, thus writes in 1727: “A great cause of this nation’s misery is that Egyptian bondage of cruel, oppressing, covetous landlords, expecting that all who live under them should make bricks without straw, who grieve and envy when they see a tenant of their own in a cart or able to afford one comfortable meal in a month; by which the spirits of the people are broken and made fit for slavery”.

A few years earlier (1718) Dr. Nicholson, Protestant Bishop of Derry, was warned by the Castle not to proceed to his diocese without a military escort. He accordingly set out from Dublin, accompanied by a troop of dragoons. The description of his journey to Derry is from his own pen. “The Executive,” he says, “were pleased to grant me a guard of dragoons, with whom I travelled in great security through the country said to be infested with a set of barbarous and pilfering tories (robbers). I saw no danger of losing the little money I had, but was under some apprehension of being starved, having never beheld such dismal marks of hunger and want as appeared in the countenances of most of the poor creatures that I met with on the road.

“The poor wretches lie in rocky sod-hovels, and have generally no more than a rag of coarse blanket to cover a small part of their nakedness. Upon the strictest inquiry I could not find that they are better clad or lodged in the winter season. These sorry slaves plough the ground to the very tops of their mountains for the service of their lords, who spend truly rack-rents in London”.

The Protestant gentry who held in their hands the whole administration of the laws, had no sympathy with the Catholic farmers, and, being practically irresponsible, threw them into prison at will, or ground them down with the greatest tyranny, and subjected them to indescribable hardships. The tenant was allowed no security in his holding. Should his industry have reclaimed some marshy tract, or cultivated the barren mountain, an enemy was sure to be at hand deeming it little less than a religious duty to deprive him of the fruits of his toil, and to drive him forth from his home unpitied and unrequited. Under such a system the Catholic tenants were reduced to the lowest degree of misery. A writer of 1766 speaks of them as “naked slaves, who labour without food, and live while they can without homes or covering, under the lash of merciless and relentless taskmasters.”

By a mockery of legislation grass lands were by Act of the [colonial] Irish Parliament exempted from the payment of the tithes. Thus, the rich Protestant proprietors became practically freed from contributing to the support of their own clergy, and the small Catholic farmers were left to the tender mercy of the tithe-proctors, who, “with all the hands of all the harpies,” plundered them to secure a rich maintenance for the alien ministers of an alien creed. The determination to crush out every Irish industry extended even to the humbles trades – on land and water. From Folkestone and Aldborough petitions were presented to Government complaining that Irishmen were allowed to catch herrings at Waterford and Wexford and to send them across the Straits for sale. Other petitions were forwarded, praying that all fisheries might be prohibited on the Irish coasts, except in boats built and manned by Englishmen. It was the remark of Dean Swift that the convenience of ports and harbours which nature bestowed so liberally on Ireland was of no more use to her people than a beautiful prospect to a man shut up in a dungeon. If, whilst England was engaged at war with a Catholic State, any Irish Protestant suffered loss from the enemy’s privateers, a tax was levied on the Catholics of the district in which he lived to restore to him the full amount of his loss. Should it happen that a Protestant was robbed, and were it supposed that the culprit was a Papist- and no very strict proofs were required, if, for instance, the robber had been heard to speak with an Irish accent, it would be enough-the loss was compensated at the expense of his Catholic neighbours. A Protestant gentleman in the County of Kilkenny, from whom property had been stolen, was compensated by a heavy tax then levied on the Catholics of his district. Very soon after, however, the robber was discovered and was found to be a Protestant. Nevertheless no restitution was made to the Catholics for the injury done to them.

Eviction of Catholic tenants

Mr. Lecky, in his “History of England in the Eighteenth Century,” having at considerable length set forth the sufferings and disabilities of the Irish Catholics, adds the following glowing eulogy on the fidelity of the Irish people: –

“They clung to their old faith with a constancy that has never been surpassed, during generations of the most galling persecution, at a time when every earthly motive urged them to abandon it, when all the attractions and influence of property and rank and professional eminence and education were arrayed against it. They voluntarily supported their priesthood with an unwearying zeal when they themselves were sunk in the most abject poverty, when the agonies of starvation were continually before them. They had their reward. The legislator, abandoning the hopeless task of crushing a religion that was so cherished, contented himself with providing that those who held it should never rise to influence or wealth, and the Penal Laws were at last applied almost exclusively to this end” (5)

Throughout the whole period of persecution in Ireland the succession of bishops and priests was never broken. As was to be expected, however, many were the sufferings of those devoted men whilst they endeavoured to minister to their flocks. It was enacted under William III that all the Catholic archbishops, bishops and regulars should depart the kingdom, under penalty of imprisonment and transportation; and should they at any time return to Ireland they were to be considered guilty of high treason, and to suffer accordingly. In 1704 another Act was passed by which only a certain number of the parochial clergy, duly registered, were to be tolerated in each county. A particular district was allotted to each one, but no other priests were to be tolerated on any account, and all save those now registered were to be banished as regulars.

New difficulties, however, soon awaited the privileged clergy. By a special clause in this Registration Act, a registered priest who would presume to take a curate to aid him in the work of the scared ministry was subjected to all the penalties enacted against the regulars; and furthermore, if he administered the Sacraments, or said Mass outside his own registered district, he incurred the same penalties. An edict was published commanding the priests thus registered to take an oath of abjuration; and as all with scarcely an exception refused to stain their consciences by such an oath, all alike were thenceforward subject to the direct penalties of the law. At any movement they were liable to be arrested, thrown into prison and sent into exile.

To better give effect to these enactments, the Irish [colonial] Parliament, in 1709, passed a resolution declaring that to inform against a priest was an honorable act, deserving the nation’s gratitude. A reward of £50 was voted for the discovery of a bishop, or vicar-general or other dignitary, and of £20 for the arrest of any other clergyman, secular or regular. Besides these Parliamentary grants, other rewards were offered from time to time by the grand juries, and as late as 1743 a proclamation was issued by the Privy Council in Dublin, offering for the conviction of a bishop or dignitary the sum of £150; for every priest, £50, and for the discovery of persons who being in the possession of a certain amount of property, had been guilty of entertaining, concealing, or relieving a priest, £200. Other Acts of Parliament offered annuities and large rewards to such of the clergy as might choose to apostastise.

But neither bribes nor threats could sever the pastors from their flocks. With heroic courage the clergy braved every peril to break the bread of life to their faithful people. Except during the short intervals of comparative peace, they were obliged to travel from district to district in disguise; and they joyfully endured the privations and humiliations and hardships to which they were every day exposed. During the day they were clad in frieze like the peasantry, and they usually carried a wallet across the shoulders, to better to conceal their ministry. Thus they passed from cabin to cabin dispensing blessings, instructing the young, and administering the Sacraments; they lived with the peasantry and partook of their humble fate, which was at all times heartily shared with them. Mr. Lecky does not fail to recognise the heroism thus displayed by the devoted clergy: –

“Their conduct,” he says, “in many respects was very noble. The zeal with which they maintained the religious life of their flocks during the long period of persecution is beyond all praise.” (6).

In the very dawn of the Reformation in Ireland [Edmund] Spenser had contrasted the negligence of the “idle ministers”, the creatures of a corrupt patronage, whom, “having the livings of a country opened unto them, without pain and without peril, will, neither for any love of God, nor for zeal for religion, nor for all the good they may do by winning souls to God, be drawn forth of their warm nests to look out into God’s harvest”, with the zeal of the popish priests, who “spare not to come out of Spain, from Rome, and from Rheims, by long toil and dangerous travelling hither, where they know that peril of death awaiteth them, and no reward or riches, only to draw the people into the church of Rome.” The same fervid zeal was displayed by the Catholic priesthood in the days of the Cromwellian persecution, and during all the long period of the Penal Laws.

Some few years ago an English gentleman paid a passing visit to the house of the venerable Bishop of Kilmore. He was very much struck by the portraits of the bishop’s predecessors which adorned the sitting-room but could not conceal his surprise that the place of honour between two of these portraits was allotted to a highland piper in full costume. Still greater, however was his surprise when he learned from the lips of the bishop that it was the portrait of one of the most illustrious of his predecessors, who, being a skilled musician, availed himself of such a disguise in order to visit and console his scattered flock.

Dr. O’Gallagher, Bishop of Raphoe, when holding a visitation in the parish of Killygarvan, in the year 1743, partook of the hospitality of its parish priest, Father O’Hegarty, whose humble residence stood on the bank of Lough Swilly. It soon began to be whispered about that the bishops was in the neighbourhood, and without delay the priest-catchers were on his track. One evening a note was handed to him from a Protestant gentleman visiting him to dinner. Whilst he read the letter, the messenger said to him in Irish, “As you value your life, have nothing to say to that man,” a hint of unintended treachery which the bishop easily understood. That night Dr. O’Gallagher retired to rest at an early hour, but as he could not sleep, he rose at midnight and resolved to depart. The good priest, however, would not listen to his doing so, and insisted on his retiring again to rest. “The way is dangerous and lonely,” he said, “and it will be quite in time for your to leave at dawn of morning.” The bishop tried again to take some rest, but sleep had fled from him, and after a short time he again rose, and long before the morning sun had lit up the cliffs of Bennagallah, Dr. O’Gallagher was on the bridle road to Rathmullen. At sunrise a troop of the military was seen hastening from Milford. They surrounded Father O’Hegarty’s house, and soon the shout was heart from them, “Out with the Popish bishop”. A local magistrate named Buchanan was their leader, and great was their disappointed when Father O’Hegarty assured them that the bishop had been there, indeed, but had taken his departure. They would have some victim, however, for they did not wish it that their nocturnal excursion from Milford had been in vain. They accordingly seized the aged priest, and binding his hands behind his back, carried him off as a prisoner. The news spread along the route and the cry was echoed from hill to hill that their loved pastor was being hurried off to prison. A crowd soon gathered, and showed their determination to set him free; but Buchanan, raising a pistol, shot him dead on the spot, and threw his lifeless body on the roadside!

No less hardships and perils awaited the Catholic clergy in the rich plains of Leinster than amid the rugged hills of Donegal. The Rev. M. Plunkett was P.P. of Ratoath and Vicar-General of the diocese of Meath. Being connected with some of the chief families in Meath, and being, besides, a man of solid piety and learning, several of the Protestant gentry sought, but in vain, to secure him some toleration in the exercise of his sacred ministry. When the agents of persecution visited the neighbourhood his wretched mud wall thatched chapel would be closed and the pastor would seek concealment in retired parts of the country. There was a priest-hunter named Thompson who singled out the zealous pastor, anticipating a rich reward for his arrest. Father Plunkett, however, was effectively concealed in the house of a Protestant magistrate, where a room was set aside for his use, with bed and fuel and provisions of every sort. The room was constantly kept locked, and it being supposed to be haunted, the servants never cared to enter. Whenever Thompson applied for a warrant this gentleman gave the priest some timely information, and then he came at night with his servant, and drawing forth the ladder which was left at hand for the purpose, he entered the room prepared for him. While the storm lasted he remained there during the day, and if there were any sick to be attend, or any sacraments to be administered, the servant would apply the ladder at night, give the signal, and the pastor would descend, attend his people, and return before the break of day. In 1727, aged 75 years, he passed to his reward. I mention his case on account of his illustrious name and family, and to show how friendly some Protestants proved. Space will permit me to give but another example: –

A priest-catcher named Harrison was particularly active in the West of Ireland. A friar named Father Cunnan was officiating in the open fields, when the congregation was set upon by this Harrison and his band. There being no time to take off the sacred vestments, the poor friar struck off, habited as he was, to Cloonmore, to the house of a Protestant magistrate who had often befriended him. The magistrate, seeing that there was no time to be lost told him to hide as best he could and snatching the vestment put it on himself, and pretended to be himself the runaway, started off by the back door over hedges and fields, the priest-hunters being quickly in pursuit. At length they captured him, and took him to town before the resident magistrate, who laughed heartily at finding the prisoner none other than his brother magistrate, who explained the matter by saying he “wished to see how those fellows were able to run”.

The conversion of Protestants in Ireland to the Catholic faith, throughout the whole period of the Penal Laws was beset with the severest pains and penalties. The convert at once forfeited all the rights and privileges which he had hitherto enjoyed. He was, moreover, regarded as an enemy of the State, and punished as such and the priest who was instrumental in his conversion became subject to the same penalties. Nevertheless, many Protestants were led to embrace the truth. At the Spring Assizes in Wexford in 1748 Mr. George Williams was adjudged guilty “of being perverted from the Protestant to the Popish religion,” and was sentence to be “out of the king’s protection; his lands and tenements, goods and chattels, to be forfeited to the king, and his body to remain at the king’s pleasure”. (7) Two years later a priest was indicted in Tipperary for “perverting a dying Protestant”; and as he did not appear for trial, he was, in usual form, presented as an outlaw by the grand jury to be punished as “a tory, robber and rapparee of the Popish religion”. (8) Notwithstanding these penalties many were converted, and must have made noble sacrifices for the faith.

The Protestant Primate, Boulter, in his letters to the Government in England, bitterly lamented that “the descendants of many of Cromwell’s officers here have gone off to popery”. And in 1747 we find renewed complaints from Galway to the effect that “of late years several old Protestants, and the children of such, have been perverted to the Popish religion…..”(9)

A Protestant, who being married to a Catholic lady, failed within twelve months to make her a Protestant, forfeited his civil rights, and incurred all the risks and penalties of a reputed Papist. At the Limerick election, in the year 1760, several voters were objected to on the ground that they had Popish wives, and in due course their votes were declared null. By another clause in the Act of Parliament any barrister, attorney, or solicitor, presuming to marry a Papist, became by the very fact debarred from continuing in his profession. A Protestant lady possessed of, or heir to, any real property, or who held personal property to the amount of £500, by marrying a Catholic forfeited her whole property, which passed at once into the hands of the nearest Protestant relative. If in a Catholic family, the eldest son declared himself a Protestant, he became entitled to the whole property; the father could no longer dispose of any portion of it, and all the claims of the other children were set aside. As Catholics could not hold land in fee, it sometimes happened that they purchased property under the name of some friendly Protestant on whose honour and integrity they thought it safe to rely. To punish evasion of the law, an Act was passed annulling all such purchases; and as an encouragement to informers, it was decreed that whoever, not being himself a Papist, would make the discovery of such a purchase, the property so discovered should become his prize.

When the child of a mixed marriage was baptized by a priest the Protestant parent became classed among the reputed Papists, and had to suffer all the penalties of such offenders. The father of Dr. Young, Catholic Bishop of Limerick, was a Protestant married to a Catholic lady. The infant was baptized by a Catholic priest. Mr. Young was immediately thrown into prison, where he was detained for a considerable time, and he was, moreover, subjected to a heavy fine. One happy result followed from this punishment. Mr. Young came out of prison a Catholic, and his son in after years became one of the holiest bishops who adorned the Irish church in those perilous times.

J.A. Froude, and not a few other hostile writers on Irish history, in modern times have asked in astonishment how it was that, despite, the tempest of persecution which swept over Ireland from the dawn of the Reformation to the close of the eighteenth century, the Irish Church preserved her unbroken line of bishops and priests to hand on the traditions of the faith and to minister to the faithful people.

The reply is given by John Mitchel, and his words present an accurate picture of the fearless devotedness and unparalleled heroism of the Catholic clergy of Ireland in those perilous days. He thus writes: –

“The matter which disquiets and perplexes the mind of Mr. Frounde is the fact that, in the midst of the horrors of oppression, Catholic priests were not only ministering all over the country, but coming in from France and Spain and Rome; not only supply the vacuum made by transportation and by death, but keeping up steadily the needful communication between the Irish Church and its head; and not coming, but going (both times incurring the risk of capital punishment), and not in commodious steamships, which did not then exist, but in small fishing luggers or schooners; not as first-class passengers, but as men before the mast. Archbishops worked their passage. The whole of this strange phenomenon belongs to an order of facts which never entered into the ‘historian’s’ theory of human nature. It is a factor in the account that he can find no place for; he gives it up. Yet Edmund Spenser, long before his day, as good a Protestant as Frounde, and an undertaker too, upon Irish confiscated estates, who had at least somewhat of the poetic vision and the poetic soul, in certain moods of his undertaking mind, could look upon such strange beings as these priests with a species of awe, if not with full comprehension. He much marvels at the zeal of these men “which is a greater wonder to see how they spare not to come out of Spain, from Rome, and from Remes, by long tyle and dangerous travaleying hither, where they know perill of death awayteth them and no reward or richesse’. ’Reward or richesse!’ I knew the spots within my own part of Ireland where venerable archbishops hid themselves, as it were, in the hole of a rock. In a remote part of Louth county, near the base of the Fews Mountains, is a retired nook called Ballymascanlon, where dwelt for years, in a farm-house which would attract no attention, the Primate of Ireland, and successor of St Patrick. Bernard MacMahon, a prelate accomplished in all the learning of his time and assiduous in the government of his archdiocese; but he moved with danger, if not with fear, and often encountered hardships travelling by day and night. Imagine a priest ordained at Seville or Salamanca, a gentleman of high old name, a man of eloquence and genius, who had sustained disputations in the College halls on questions of literature or theology; imagine him on the quays of Brest, treating with the skipper of some vessel to let him work his passage. He wears tarry breeches and a tarpaulin hat, for disguise was generally needful. He flings himself on board, takes his full part in all hard work, scarce feels the cold spray and the tempest. And he knows, too, that the end of it all for him may be a row of sugar-canes to hoe under the blazing sun of Barbados, overlooked by a broad-hatted agent of a British planter. Yet he goes early to meet his fate, for he carries in his hand a sacred deposit, bears in his heart a sacred message, and must deliver it or die. Imagine him then springing ashore and repairing to seek the bishop of the diocese in some cave or behind some hedge, but proceeding with caution by reason of the priest-catchers and other wolf-dogs. But Froude would say: “This is the ideal priest you have been portraying. No, it is the real priest, as he existed and acted at that day, and as he would act again in the like emergency. And is there nothing admirable in all this? Nothing sublime? I should like to see our excellent Protestantism produce fruit; like this?”

Next to the devoted clergy, the Catholic schoolmasters suffered most. About the same price was set on a priest, a schoolmaster, and a wolf, or wild beast. Sometimes even bloodhounds were set upon the track of the Catholic schoolmaster, on the mountain or in the woods! Year after year men were thrown into prison and sentenced to transportation for the sole crime of imparting knowledge to Irish youth. Nor are we to suppose that being transported was a light penalty. Those transported were treated as slaves. Mr. Froude admits that they “were sold to the planters in the colonies” (10) that thus they might defray in their persons the expense of transporting them. By such laws and such penalties it was vainly hoped that barbarism would be enforced upon the Irish people, or that the Catholic youth of Ireland, in their eager desire for knowledge, would drink it in at the poisoned sources of heresy. While, however, the hedge schools produced excellent classical scholars, the Government schools miserably failed and were attended with the worst results, though they were richly endowed, and had been established for the avowed purpose of reclaiming Irish youth from Popery to “Protestantism and good manners.”

The Penal Laws were at first mainly aimed at the clergy and other leaders of the Catholic body. Death, imprisonment, or banishment awaited the Bishop and the Priest. Confiscation, ruin and exile were the lot of the landed proprietors and wealthier class, unless they renounced their faith. It was hoped that thus the mass of the people, deprived of their leaders, would, through apathy or ignorance, be gradually led to embrace the Protestant tenets. As years went on, however, that delusion vanished. No such result ensured, and hence everything was done by the persecutors to crush out the very lifeblood of the Irish Catholic peasantry.

In view of such facts Lord Macaulay might well speak thus –“It is not under one, or even twenty, administrations, but for centuries, that we have employed the sword against the Catholics of Ireland. We have tried famine, we have had recourse to all the artifices of draconian laws, we have tried unbridled extermination, not to suppress or conquer a detested race, but to eradicate every trace of this people from the land of its birth. And what has come of it? Have we succeeded? We have not been able to extirpate or even to weaken them. They have increased successively, notwithstanding all our persecutions, from two to five, and from to seven millions. Ought we then to return to the superannuated policy of former days, and render them yet stronger by persecution? I know history. I have studied history, and I confess my incapacity to find in it a satisfactory explanation of this fact. But if I were able, standing beneath the dome of St. Peter’s at Rome, to read with the faith of a Roman Catholic the inscription traced around ‘Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it’, then, indeed, I could solve the problem of Irish history”.

“Persecution only purified the Irish Church; the faith, having passed through the crucible of every trial, only shone forth the more brilliantly, thereby showing to the world that God was its Author and God was its Defender. If the wicked ingenuity of the statesman, if the word of the warrior, if the axe, the gibbet, the halter of the executioner, if all the wealth and talent of a mighty nation – in a world, if all the power of earth and hell leagued together could extinguish the faith of a nation, then, surely, the praises of Jesus and Mary must have long ‘since died out in our country’. ‘ I know not’, wrote Lord-Deputy Chichester in 1745, ‘how the attachment to the Catholic Church is so deeply rooted in the hearts of the Irish, unless it be the soil is infected with Popery!’ Deep into the soil of the hearts of the Irish people St. Patrick laid the foundations of the Church of Ireland. She has seen the snows of 1,500 winters; and centuries of unparalleled persecutions by the Danes, and still more by the English assailed her in vain. If perseverance in the Faith under unheard of persecutions of every kind be a test of a nation’s fidelity, the sixteenth and seventeenth, as well as the seventh century, may be called the Golden Age of the Irish Church.

“Hence, Ireland’s claim to her honoured title ‘Catholic’ remained as strong and indisputable as ever it had been; that in feeling, character, numerical strength, she continued the devoted child of the Church, that persecution only increased that attachment to her priests and that loyalty to her Faith which had been cemented in the blood of her children for 300 years, and which furnished a spectacle as rare as it was heroic – a whole nation suffering everything, sacrificing everything, even life, in her determination to cling to the old Faith of her fathers”. – Dean Kinane

Now, to what has all – under Providence and the protection of St. Patrick – to be attributed but to the fidelity and the inseparable union of the Priests and the People, who have always stood by one another so nobly and so unselfishly, and who, please God, will continue to stand together to the end, in spite of the aspersions of one or two undutiful sons, who call themselves Irish and Catholic, and wish to be regarded as such, but who prove by their lives and their writings that they are neither one nor the other. People cannot be true to Ireland, no more than to their Religion, without being true to their Priests! We might apply to our Priests, as well as to our mothers and our country, the words that a Poet has written of his Alma Mater: –

“Our childish hearts she drew to her

To foster them and cherish.

No good is ours but due to her –

How could we be untrue to her,

And suffer love to perish?”

A cruel grinding policy on the part of the Government forced vast numbers of the peasantry, or poorer classes, in to the ranks of the Whiteboys and similar associations and led to the Rebellion of 1798, when so many suffered and died for Faith and Fatherland.

We leave it to others to treat of that unhappy epoch in Irish History – it would take a large volume to do justice to it – and we conclude in the words of Father Burke: –

“We see the providence of God in the labour of Ireland’s glorious Apostle. Who can deny that the religion which St. Patrick gave to Ireland is divine? A thousand years of sanctity attest it; three hundred years of martyrdom attest it. If men will deny the virtues which it creates, the fortitude which it inspires, let them look to the history of Ireland. If men say that the Catholic religion flourishes only because of the splendor of its ceremonial, the grandeur of its liturgy, and its appeal to the senses, let them look to the history of Ireland. What sustained the faith when church and altar disappeared? When no light burned, no organ pealed, but all was desolation for the Church, of which the external worship and ceremonial are but the expression. But if they will close their eyes to all this, at least there is a fact before them – the most glorious and palpable of our day – and it is, that Ireland’s Catholicity has risen again to even more than her former glory! The land is covered once more with fair churches, convents, colleges, and monasteries as of old. And who shall say that the religion that could thus suffer and rise again is not from God?

“What is the future to be? What is the future that is yet to dawn on this dearly-loved land of ours?. The past is the best guarantee for the future. Oh, how glorious will that future be, when all Irishmen shall be united in one common faith and one common love! Oh, how fair will our beloved Erin be, when clothed in religious unity, religious equality and freedom, she shall rise out of the ocean wave, as fair, as lovely, in the end of time, as she was in the glorious days when the world entranced by her beatify, proclaimed her to be the mother of saints and sages. Yet I behold her rising in the energy of a second birth, when nations that have held their heads high are humbled in the dust!

As so I hail thee, O, Mother Erin! And I say to thee –

“The nations have fallen, but thou still set young:

Thy sun is but rising when others have set;

And though slavery’s clouds round thy morning have hung,

The full noon of Freedom shall beam round thee yet!”

(1) Introduction to the Life of Dr. O’Hurley, Archbishop of Cashel, by Dean Kinane

(2) Ibid

(3) The Catholics of Ireland under the Penal Laws in the Eighteenth Century by Cardinal Moran

(4) Morley’s Burke, p. 101

(5) Lecky, History, II, pp. 256, 386

(6) Lecky, History, II, p. 282

(7) See Gentleman’s Magazine for April, 1748

(8) Irish Record Office, Presentments of Grand Juries, 1750

(9) Boulter’s Letters, 11, 12; Hardiman’s Galway, p. 188

(10) Froude, The English in Ireland, 1, p.593

Posted on September 29, 2010, in Anglicanism, CATHOLIC PAMPHLETS, Irish History, Mass, Persecution. Bookmark the permalink. Leave a comment.

Leave a comment

Comments 0